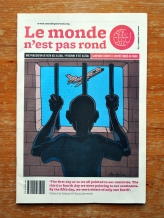

The Le monde n’est pas rond blog has been silent for a while. Partly because we’re sifting through submissions – many of excellent quality – that we’ve received for the next issue of our newspaper. Partly because we’re applying for cultural funds to offset the printing and design costs of our future issues. But there’s another reason, closer to home. Le monde n’est pas rond is based in Luxembourg, but ‘home’ means the island of Malta, which is where the editor (myself, Antoine Cassar) and the designer (Marco Scerri), both currently living as expats further north (or emigrants, or immigrants, what’s the difference?), hail from.

It all began on Tuesday 9th July, a dark day for Malta. In a speech given at the Malta Chamber of Commerce regarding the creation of a Citizenship and Visa Agency to alleviate bureaucracy for “potential investors”, Joseph Muscat, the new Prime Minister, exclaimed:

“Once they know what Malta has to offer, we are in a great position, because we have a killer proposition.”

Unfortunately, this was not the only “killer proposition” that our PM had made that same day: a few hours earlier, Muscat ordered Air Malta to prepare a plane to deport a group of 45 young Somali men to the military airport of Mitiga, 8 km outside of Tripoli, Libya. The deportees had arrived in Malta by boat that very morning, and were due to be forcibly ‘pushed back’ to Libya at midnight.

Thankfully, the swift action of a handful of lawyers and grassroots NGOs caught the attention of the European Court of Human Rights, which immediately issued an interim order blocking the mass deportation. The Maltese government obeyed, but assured that it had not been bluffing and remained ready to “consider all options”, including not only the failure to offer protection to beleaguered, vulnerable individuals, but also the forced transportation of the same people back into the jaws of danger. The last time Malta enacted a ‘pushback’, in 2002 at the hands of the Nationalist government now in opposition, a group of Eritreans were tortured upon arrival in their country. That decision was subsequently condemned in a report by Amnesty International.

Notwithstanding Malta’s agreement to comply with its international legal obligations, the ‘heroic’ threat of deportation had given rise to an intense wave of racist expression in the streets and on the internet, including various insults of a sexual nature, the waving of flags where the Maltese Cross took the place of the swastika, and a public list of “traitors” compiled “one by one”. Two days later, on Thursday 11th July, the Prime Minister publicly condemned, in unequivocal terms, the xenophobic language that had smothered the island over the past three days, and adamantly discouraged the demonstration that the extreme right had been planning for the following Sunday in Valletta. Luckily, the Maltese-style Nuremberg Rally did not materialise. Muscat’s official disapprobation of xenophobia is to be appreciated (and I should admit, it took me by surprise), but it came a little too late – the racist violence had already begun, with physical attacks on two African bus drivers in the north of the island.

Members of the Maltese artistic community had also been quick to react. Karl Schembri, a journalist and writer currently based in the Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan with Oxfam International, wrote a hard-hitting letter to the Prime Minister, condemning his populist rhetoric, exhorting him to make his political points with fellow politicians rather than with the lives of vulnerable people, and declaring that the blood of innocent victims that would stain the hands of the Maltese government would not be in Schembri’s name. Immanuel Mifsud and four other Maltese authors followed suit; based on their letters, a common statement was drawn up, and signed by around 30 writers. Maltese academics and graphic artists brought out their own analogous statements.

“There is no enemy beyond your shores. Look for your enemy, instead, at the bottom of yourself.” – Annalise Falzon. Meme by Wayne Flask

Meanwhile, Maltese xenophobic forums (including, irony of ironies, a number of Maltese emigrants) were supporting their ‘arguments’ with quotations from Maltese Romantic poets, the national anthem, and even words of the Dalai Lama. After discussion with fellow writers, on Friday 12th July, I decided to create a website bringing together the wide variety of Maltese artistic expression on the theme of migration. Loosely based on the model of Solidarity Park, which publishes rolling poems in support of the peaceful çapullers of Gezi Park, the blog Mhux F’Isimna (Not in Our Name) features art, film, photography, music, poetry (including translations from other languages), short stories and articles in Maltese and English. Against the policy of deportation and xenophobia, in favour of fundamental human rights (particularly Articles 13 and 14 of the UDHR) and human dignity, the contributions received are published in solidarity with those who were forced to abandon their countries, and found themselves migrating from one cage to the next.

Among the contributors are a number of members of the grassroots NGO Konnect Kulturi – Integra, who were among those at the forefront of the protests on 9th July in front of the Police Headquarters (where the Somali men, women and babies who had arrived that morning were kept, sleeping on the floor, whilst the deportation plane was being prepared), and were among those targeted with sexual insults by prominent members of the extreme right. Jean Paul Borg, who teaches Maltese to Africans in Malta on a voluntary basis on behalf of Konnect Kulturi, sent in a short story detailing his experience of that dark day of Tuesday 9th, and the relief of himself and his students when the news came in of the blocked deportation. “Din id-darba kelli naqsam il-messaġġ magħhom. It-tbissim kien universali. / Ħassejt dehxa. Ikkonfermajt li għandi xi ħaġa fuq ix-xellug ta’ sidri li taħdem.” (“This time I had to share the message with them. The smile was universal. / I felt a shudder. And I confirmed that there is something on the left side of my chest that works.”)

As of 27th July, twenty-nine artistic contributions have been featured on Mhux F’Isimna, including a few works published in Issue 1 of Le monde n’est pas rond or due to appear in Issue 2. The door remains open to artists in or linked to Malta. The variety of angles, rhythms and styles exploring the realities of migration and borders is highly interesting, profoundly human, and may eventually be a good basis for the publication of a printed anthology, or perhaps for a Maltese edition of the newspaper (Id-Dinja Mhix Tonda). Deep down, however, I wish that these projects were ephemeral, and unnecessary. For as long as borders and nation-state fantasies continue to impose their racist heirarchy upon the peoples of the world, and for as long as freedom of movement remains proportional to the GDP of one’s birthland or the melanin content in one’s skin, our work will continue.